Twice Algeciras: Italian blood in combat diving against the Royal Navy

22 September 1975, the frigate ARA Santissima Trinidad was under construction at the Río Santiago shipyard near Buenos Aires for the Argentine navy. On this date, an explosion occurred on her hull. The explosion was the result of an improvised hull mine installed by divers from the "Montoneros" organization, which was engaged in disputes with the Argentine government (the ship's construction was completed in the early 1980s). The perpetrators of the action have been arrested, among them, the most expert in diving activities has been recruited for advice on the subject...

02 April 1982, with Operation Rosario, Argentine forces landed in the Malvinas/Falklands Islands archipelago, a disputed territory with the United Kingdom. The action triggered a series of actions in the diplomatic and military field, the United Kingdom sent a Task Force to the South Atlantic, commanded by submariner Admiral John Forster "Sandy" Woodward. With lines of communication greatly stretched from the UK to the disputed islands in the South Atlantic, British forces use Ascension Island and Gibraltar as support points for their operations to counter the Argentines.

Mare Nostrum, the Italian pioneers

In the First World War, the Regia Marina, the Italian Navy, by means of small boats carrying explosives managed to destroy some ships of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Based on this concept, in the 1930s, members of the Italian navy developed manned submersibles, or popularly "human torpedoes" (today, it would resemble a Diver Propulsion Device) so that, using the stealth of immersion, they could penetrate port defences and install explosive charges on their targets. The invention was called SLC (Siluro a Lenta Corsa- slow-moving torpedo) and nicknamed Maiale, pig in the Italian language, for its constant technical "temperaments" that made operation difficult.

In 1938, the Italian navy created the Gamma Group, a unit of swimmers/divers for attack and sabotage actions.

With the outbreak of the Second World War (WWII), Regia Marina used its previous experience against its adversaries. In 1941, the Gamma Group was incorporated into Decima Flottiglia, MAS, a unit which would be responsible for operating fast boats and SLCs from submarines.

In the Mediterranean theatre of operations, Decima Flottiglia wrote its history, inspiring the emergence of similar units in Germany, the UK and the USA. One of the most emblematic actions of the Decima Flottiglia took place in Alexandria in December 1941.

Alexandria, Egypt, 1941

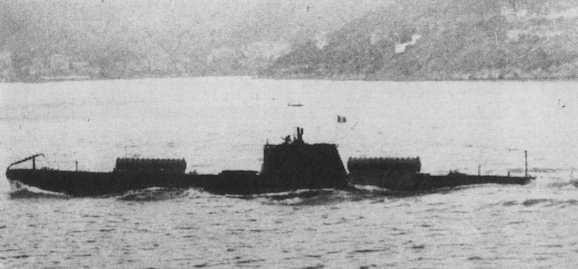

The action at Alexandria was the climax of a would be of attempts to attack this port with submarines/diver in their SLCs. The first attempt occurred with the submarine Iride, attacked by RAF (Royal Air Force) planes it was destroyed among the crew members was the diver Teseo Tesei, one of the creators of the SLC, who later died in another action by Decima Flottiglia. The second attempt had no better fate: the submarine Gondar was attacked by escort ships and all its crew captured, among them another creator of the SLC, Elios Toschi. The third attempt began on December 3, 1941, when the submarine Sciré, commanded by Corvette Captain Julio Valerio Borghese, suspended from La Spezia on Italy's west coast with three SLCs on board. The navigation of the Sciré sought the Greek island of Leros, where the Italian navy had facilities, in this place, the divers would be embarked.

During the defeat to Leros, the Sciré was sighted by a British plane, it was not attacked, because it responded correctly to the mutual identification signal to the British crew, which in that period in struggle, were green light signals (the Sciré had this information thanks to the intelligence of the Italian navy). After the rendez-vous in Leros, six divers joined the submarine and proceeded to Alexandria.

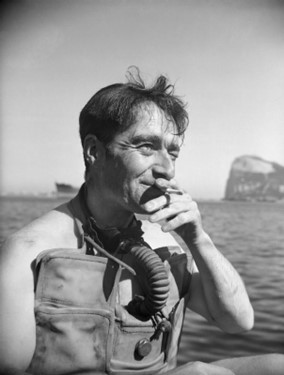

On the night of 19 December 1941, about 1.3 nautical miles north of Alexandria harbour, the SLCs with their divers set off from Sciré towards their targets. This variety of alternatives and concealments created confusion for the defences of the port of Gibraltar, who believed they were being attacked by U-boat torpedoes, or, when they discovered they were the actions of divers, thought they were operating from submarines. The Royal Navy sought to strengthen its defences and installed sentries, searchlights, acoustic devices, naval patrols and organised a group of divers to inspect its ships. The Royal Navy divers operated in rudimentary conditions, using Davis underwater escape apparatus as their diving equipment, and had no fins or suits. In this group of Royal Navy divers was the then CT Lionel "Buster" Crabb. Crabb and his group gradually developed techniques and, with material captured from the Italians, increased their own operation. Crabb would have been the idealiser of the procedure of launching explosive charges of little more than 1kg in the water, periodically, by speedboats or dinghies as a protective measure against submerged invaders. Crabb would also have been suspicious of the use of Spanish territory and of Otterra, but these suspicions were not in vain: British intelligence, with the participation of a double agent, the "Queen of Hearts", Larissa Swirdiski, a Russian emigrated by the 1917 revolution in her country, would have begun to uncover the actions of the Italians.

Once again, Gibraltar...once again, Algeciras...1982

With tensions between the United Kingdom and Argentina and their respective mobilisations for a confrontation over the dispute of the Falklands/Malvinas Islands, the Argentine navy selects a group of divers to attack Royal Navy ships in Gibraltar. This attempt is conceived and commanded by Admiral Jorge Isaac Anaya, commander of the Argentine Navy. The group received instructions and left on commercial flights to Europe with false passports at the end of April, on arriving in the Old Continent, they received the explosive charges, Italian "limpet mines" from Argentine emissaries in Spain. The group settled in the region of Algeciras, Spanish territory, which shares the waters and views of Algeciras Bay with Gibraltar, thus allowing observation and reconnaissance to attack UK ships. To build a cover for their actions, they went to the department stores' "El Corte Inglés" where they bought dinghies and fishing gear to make up the pretence that they were fishermen frequenting the region.

The established protocol was to report to the command of the operation, which would issue or not the authorization to proceed. Initially, they communicated the possibility of attacking a minesweeper (considered to be of little value, and authorisation was denied), as well as oil tankers, which were also denied because they did not target civilian vessels or those of other nationalities and avoided environmental damage.) Reporting the presence of other military battleships in the port (this time, compensatory targets, they were not given permission to attack them, as according to the upper echelon, diplomatic talks were underway and action against Royal Navy ships would jeopardise a possible agreement).

This refusal to attack occurred on 2 May 1982, on this same date, Frigate Captain Chris Wreford-Brown and his crew undertook actions which enabled them, on their return to base 62 days later, to hoist the "Jolly Rogers" flag, the pirate flag, symbol of victories at sea by British submarines. Wreford-Brown was the commander of the nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror, which sank the Argentine cruisers ARA Belgrano.

After the loss of the Belgrano, conditions were relaxed for Argentine divers to carry out the attack (it should be noted that on April 25, British FT had already retaken the South Georgian Islands archipelago, where the Argentine navy had lost the submarine ARA Santa Fe, and on May 1, Argentine positions in the Falklands/Malvinas Islands had been bombed for the first time by aviation). When the British frigate HMS Ariadne arrived in Gibraltar, they decided that this would be the target and began preparations to consummate the attack. However, the moment one of the members of the group went again to the car rental company to renew the contract, he was surprised and approached by the Spanish police, leading to the arrest of all of them.

There are several versions or an overlapping of factors to explain what led to the group's arrest:

In 1982, Spain would host the World Cup, causing public security arrangements to be more alert, present and heightened due to threats from the Basque separatist group ETA. Furthermore, the behaviour of the Argentine group would have aroused the car rental company's suspicion when making payments in cash, causing the company to alert the police. Part of the group had arrived in Europe via Paris, at Immigration, one of the members would have been detained for further investigation and later released. Did Paris and/or London know something and were they cooperating?

Spain, which also has a territorial dispute with the United Kingdom (precisely Gibraltar), could have omitted and cooperated with the Argentine presence? or would it have collaborated with its European neighbours? At the time of the events, Spain was on the eve of joining NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation). If it had been warned of the Argentine presence, would it not have collaborated with its military allies?

According to some versions, British intelligence was aware of the plan to attack Gibraltar by intercepting communications between Buenos Aires and its embassy in Madrid. London, for its part, would have requested support from the Spanish (it is widely reported in various works on the Falklands War that Argentine communications were being accessed by the United Kingdom). Among those arrested by the Spanish was Máximo Nicoletti, the same man who years earlier had dived and attacked the ARA Santissima Trinidad with a limpet mine.

The Nicoletti family...arrives in Porto Belo

Máximo Nicolleti was born in Argentina and is the son of Bruno Nicoletti and nephew of Giuseppe Nicolleti, both Italians. Bruno, in his youth, sailed on ships to travel the world and Giuseppe belonged to his country's navy in the 2nd World War, where he had contacts with members of the Decima Flottiglia. After the conflict, they emigrated to Argentina, where they dedicated themselves to various activities, being the most successful related to diving activities, establishing a trade of equipment and manufacturing of suits (initially rubber and later neoprene, where they were pioneers in the introduction of the material in the region), in this commercial activity, was present the partnership with the fellow countrymen of the company Cressi. Coincidence or not Giusseppe served with Luigi Ferraro. During the war, Ferraro operated from Turkey to Decima Flottiglia attacking merchant ships. In the post-war period, Ferraro was part, together with Jacques Cousteau, of the first presidency of CMAS (Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques) and also, was executive of Cressi equipment.

Besides being entrepreneurs in the business, the brothers are also enthusiasts and practitioners of the activity, and the Argentine diving community recognises their names as being pioneers and promoters.

The know-how with wetsuits for aquatic activities would have led Giuseppe, Seu Pino, as he was known, to be part of the beginning of a Brazilian surf material company, Mormaii. In the 1980's, Giuseppe, travelled to Brazil and started in Santa Catarina, Porto Belo, a new home and enterprise, also dedicated to the manufacture of neoprene wetsuits and equipment, the factory, which exists until today, takes his nickname ... Pino.

And if...

Would the Argentine action in Gibraltar have changed the destiny of the Falklands conflict? The fact is that HMS Ariadne did not even take part in the conflict. What if the attack had occurred earlier? Apparently, ships that made up the UK's FT and took action in the Falklands War were no longer in Gibraltar when the dive team arrived in Spain. What then, would be possible advents of a successful action in Gibraltar? Disseminate concern in the British forces? Would the British be more cautious for future amphibious landings, allowing greater exposure to attacks by Argentine forces? Infringe damage to the enemy military effort?

Would the possible advents offset a more incisive reaction from London or escalation of the conflict? Actions in mainland Argentina, for example (however, even before the group's departure, there were already signs of UK operations on the continent: on 18 April 1982, a Sea King helicopter carrying troops from SAS commandos claimed technical problems and landed on a beach in Punta Arenas, Chile, from a possible reconnaissance of Argentinean aviation bases); or even European and US disapproval?

Or would the risks outweigh the consequences and international embarrassment? Given that most of the group was composed of former members of the "Montoneros" and their insurgent past would make them likely not to officially involve Argentine authorities (however, there would be at least one member of the Argentine navy in the group as a member).

It is not intended to give correct answers, only to encourage reflection in a healthy way.

Conclusion and Legacy

History records other examples of similar actions using diving and underwater demolitions: conflicts between Israel and Arab countries and terrorist groups, Vietnam, Operation JackPot (Bangladesh versus Pakistan), the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior by the French in New Zealand, actions against piracy, the threat to naval communication lines and fuel production platforms in the Persian Gulf, with several cases of ships being targeted for sabotage by clandestinely installed explosive devices.

Years after Decima Flottiglia, sending men underwater to attack targets remains an available and evolving option for naval forces, and a threat that must be defended against. Relatively low cost, they can achieve tactical, operational and strategic objectives from large scale, surprise the opponent and generate important consequences to the precious naval communication lines or to the means and installations of interest to be neutralised.

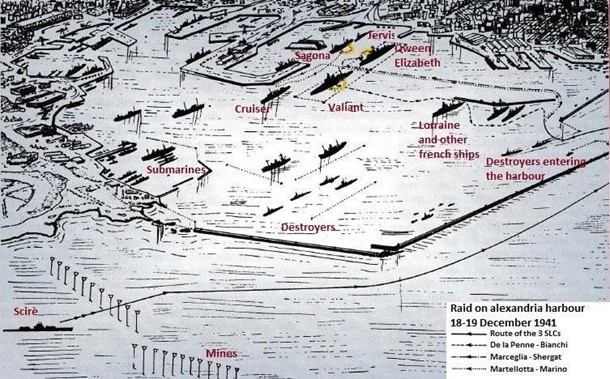

The three pairs had to overcome the port and ship defences (barriers and nets, depth charges launched at regular intervals from patrol vessels). On this night, some Royal Navy ships, were returning to Alexandria, creating the need to open the barrier protecting the waters of the port manoeuvring basin, taking advantage of this movement, the SLC operators guided their Maiales to the targets.

The HMS Queen Elizabeth was the target of the divers Marceglia and Schergat, they installed the explosive in the hull of the ship and headed for land, where they spent a few hours unscathed, posing as Frenchmen, until they were captured by the Egyptian police at a train station, seeking to embark for an extraction point.

The HMS Valiant, commanded by Sea and War Captain Charles Morgan, was targeted by Lieutenant De La Penne and Petty Officer Bianchi, De La Penne and Bianchi's SLC presented problems, sinking, nevertheless, the duo managed to install the explosive charge on the ship. With these mishaps, the divers rose to the surface and were captured by the crew of the Valiant.

Martellota and Marino, the third pair, were aiming for the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle, however, the Eagle was not on site, so they set their explosives on a target they judged to be of value, the tanker Sagona. In the vicinity of the Sagona was the HMS Jervis. Martellota and Marino swam to the pier and were captured by port security.

De La Penne and Bianchi were interrogated on the Valiant, while Martellotta and Marino were taken to the British base command. Neither revealed further information and, at the scheduled moment, explosions echoed through Alexandria harbour.

All ships (including HMS Jervis) suffered damages that required an extensive period of repairs, including docking.

The attack on Alexandria decreased Royal Navy pressure on the transport of supplies from Italy to Libya, as well as, hampered British supply convoys, departing from Egypt to supply and sustain the resistance on the island of Malta.

As the war unfolded, Italy experienced a period with two governments: one still pro-Axis and the other pro- Ally. This division was also reflected in Decima Flottiglia, so that each group continued to undertake its actions, now on opposite sides. This "Diaspora" allowed the Allies access to Italian expertise and equipment, considered at the time, as superior to the UK and US units.

After the war, many members of the Decima Flottiglia undertook activities that permeated military, commercial or sport diving.

De La Penne, who attacked the Valiant, when decorated by an Italian commendation in the service of the Allies (fruit of the split of the Decima Flottiglia) was asked to be decorated by the now, Rear Admiral Charles Morgan, commander of the Valiant (years later, Admiral Morgan was one of those responsible for turning a certain ship into a museum, this ship, is the HMS Belfast, which, whenever possible, welcomes visitors from London to dock on its starboard side in the waters of the Thames).

De La Penne, in the 1950s, was Naval Attaché of Italy in Brazil, and also, reached the Admiralty. The Italian navy honoured him by naming a class of ships after him: the "Durand de La Penne" (two units built).

Alexandria was a focal point in the campaign of the Italian submarines and divers, but, many credit this success to the forging of earlier actions where they gained experience and perfected their operations. In this past history, one of the stages was Gibraltar.

Gibraltar, near Algeciras, 1940s

Gibraltar, a strategic point that dominates the entrance to the Mediterranean through the Strait of the same name, is a British possession located in Spanish territory. Due to its relevant geographical position, Gibraltar and its surroundings are the stage of many stories, events and disputes, and it was no different in the 2nd World War.

Being a British base in the Mediterranean, the ships in Gibraltar were targets for Decima Flottiglia's actions. Initially, the divers were launched from submarines with their SLCs (before Alexandria, Borguese and his Sciré took part in some operations in Gibraltar), but also, there were variations: swimming from the Spanish region of Algeciras (Spain was officially neutral in WW2- the Italians operated from an estate known as Villa Carmela where they maintained cover to observe the enemy port and launch their attacks.

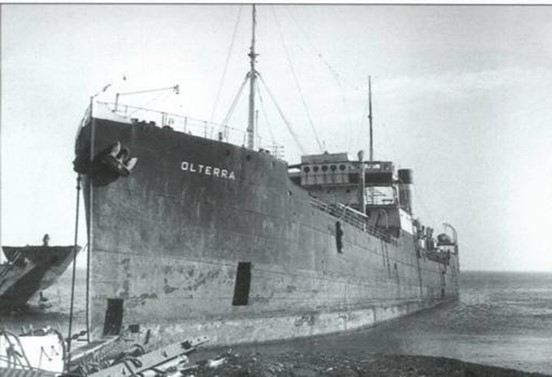

Another expedient that the Italians used was the merchant ship Olterra: an Italian vessel that, when war was declared between Italy and the United Kingdom, was in Gibraltar, its crew, to avoid being interned and/or having the ship confiscated by the British, ran the vessel aground in Spanish waters.

Subsequently, under the guise of a ship repair company, Decima Flottiglia operated from the Olterra where it provided workshops, armouries and an opening in the hull for SLCs to be launched and recovered from.

Photo 1-Submarine Sciré sailing with the SLCs.https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/Sciré-italian-royal-navy- sub.html?adblock=1&chrome=1

Photo 1-Submarine Sciré sailing with the SLCs.https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/Sciré-italian-royal-navy- sub.html?adblock=1&chrome=1 Photo 2-Detail of the SLC.https://comandosupremo.com/decima-mas-attack-on-alexandria/

Photo 2-Detail of the SLC.https://comandosupremo.com/decima-mas-attack-on-alexandria/ Photo 3-Diagram attack on the port of Alexandria. https://comandosupremo.com/decima-mas-attack-on-alexandria/

Photo 3-Diagram attack on the port of Alexandria. https://comandosupremo.com/decima-mas-attack-on-alexandria/  Photo 4-Bay of Gibraltar/Algeciras with Gibraltar on the left (where the rock formation stands out) and Algeciras on the righthttps://vivacampodegibraltar.es/campo-de-gibraltar/1017672/la-poblacion-del-campo-de-gibraltar-en- 2021-crece-en-726-personas-hasta-las-273530/

Photo 4-Bay of Gibraltar/Algeciras with Gibraltar on the left (where the rock formation stands out) and Algeciras on the righthttps://vivacampodegibraltar.es/campo-de-gibraltar/1017672/la-poblacion-del-campo-de-gibraltar-en- 2021-crece-en-726-personas-hasta-las-273530/  Photo 5-Olterra ship (note on the side, near the bow) opening for launching the SLCs. https://sevilla.abc.es/andalucia/cadiz/sevi-olterra-caballo-troya-italiano-gibraltar- 202107310824_news.html

Photo 5-Olterra ship (note on the side, near the bow) opening for launching the SLCs. https://sevilla.abc.es/andalucia/cadiz/sevi-olterra-caballo-troya-italiano-gibraltar- 202107310824_news.html

Bibliographic Sources

- MANFRIM, B.H. Cruz (2009). The Recapture of the Malvinas Islands. Villegagnon Magazine, no.04, p.104-108. SÁNCHES, Alfonso Escuadra. (2014). La Base Secreta de Villa Carmela. Almoraima Magazine, no. 41.

- BARBOZA, Walter (2015). Máximo Nicoletti: de la Santísima Trinidad a la "Operación Algeciras". Available at: < https://revistaeltranvia.com.ar/maximo-nicoletti-de-la-santisima-trinidad-a-la-operacion-algeciras/> Accessed on 07 Feb. 2022.

- Canal 12 Web. Homenaje a pioneros del buceo: Pino Nicoletti. Youtube, 06 Jan. 2022. Available at: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mK7zTN8JKc&ab_channel=Canal12Web>. Accessed 04 Feb. 2022.

- Historiograph. When Six Men Sunk Two Battleships - The Raid on Alexandria. Youtube, 19 Dec. 2020. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2vk8EC7LDRE&ab_channel=Historigraph>. Accessed 16 Feb. 2022.

- La empresa. Consulted on 07 Feb. 2022. Available at: < https://lacasadelbuceador.com/la-empresa/>.

- LUIGI DURAND DE LA PENNE. In WIKIPÉDIA, the free encyclopedia. Available at: < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Durand_de_la_Penne>. Accessed 16 Feb. 2022.

- LUIGI FERRARO. In WIKIPÉDIA, the free encyclopedia. Available at: < https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Ferraro_(militare)>. Accessed 06 Feb. 2022.

- MAFRA, Alcides & FURTADO, Thiago, (2017). Giuseppe Nicoletti, The Man from the Bottom of the Sea. Available at: < https://www.retratosdeportobelo.com.br/o-homem-do-fundo-do-mar/>. Accessed on 18 Feb. 2022.

- OPERACIÓN ALGECIRAS. Direction: Jesús Mora. Production: Co-production Argentina-Spain; Zeta Films / Aquelarre Servicios Cinematográficos / Nisa Producciones / Barakacine Producciones. Argentina/Spain. 2004.Youtube, 16 Sep.2018. 1h28minutes. Available at: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s7jzN1Y8z7o&ab_channel=IgnacioSantolin>. Accessed on 28 Jan. 2022

- Kings and Generals. Mediterranean War: Italian Raids on Alexandria and Gibraltar. Youtube, 18 May 2021. Available at: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zn4Gjueziig&ab_channel=KingsandGenerals>. Accessed 12 Feb. 2022.